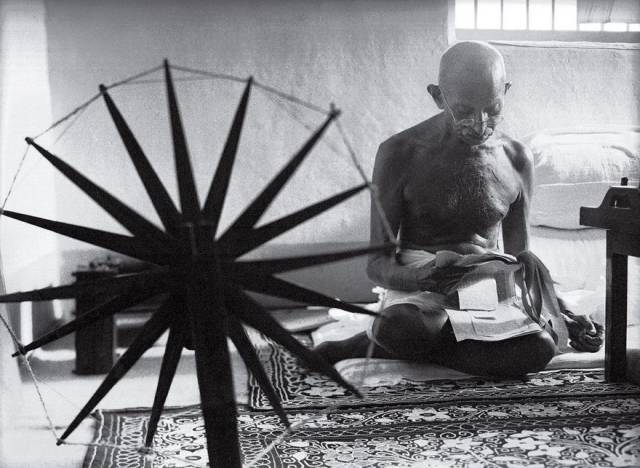

Gandhi And The Spinning Wheel, Margaret Bourke-White, 1946 When the British held Mohandas Gandhi prisoner at Yeravda prison in Pune, India, from 1932 to 1933, the nationalist leader made his own thread with a charkha, a portable spinning wheel. The practice evolved from a source of personal comfort during captivity into a touchstone of the campaign for independence, with Gandhi encouraging his countrymen to make their own homespun cloth instead of buying British goods. By the time Margaret Bourke-White came to Gandhi’s compound for a life article on India’s leaders, spinning was so bound up with Gandhi’s identity that his secretary, Pyarelal Nayyar, told Bourke-White that she had to learn the craft before photographing the leader. Bourke-White’s picture of Gandhi reading the news alongside his charkha never appeared in the article for which it was taken, but less than two years later life featured the photo prominently in a tribute published after Gandhi’s assassination. It soon became an indelible image, the slain civil-disobedience crusader with his most potent symbol, and helped solidify the perception of Gandhi outside the subcontinent as a saintly man of peace.