Thereafter, DELAG used the Graf Zeppelin on regularly scheduled passenger flights across the North Atlantic, from Frankfurt-am-Main to Lakehurst. In the summer of 1931, a South Atlantic route was introduced, traveling from Frankfurt and Friedrichshafen to Recife and Rio de Janeiro. Between 1931 and 1937 the Graf Zeppelin crossed the South Atlantic 136 times. The trips took about four days in each direction, and a one-way ticket was about $400, which translates to about $7,050 in today’s money.

In 1936, DELAG introduced the Hindenburg, which made 36 Atlantic crossings (North and South).

Its interior was designed by Fritz August Breuhaus, who also took part in designing Pullman coaches, ocean liners, warships of the German Navy, and so on.

Hindenburg’s Dining Room was approximately 47 feet in length by 13 feet in width, and had paintings on silk wallpaper by Professor Otto Arpke on its walls, depicting scenes from Graf Zeppelin’s flights to South America.

Dining Room

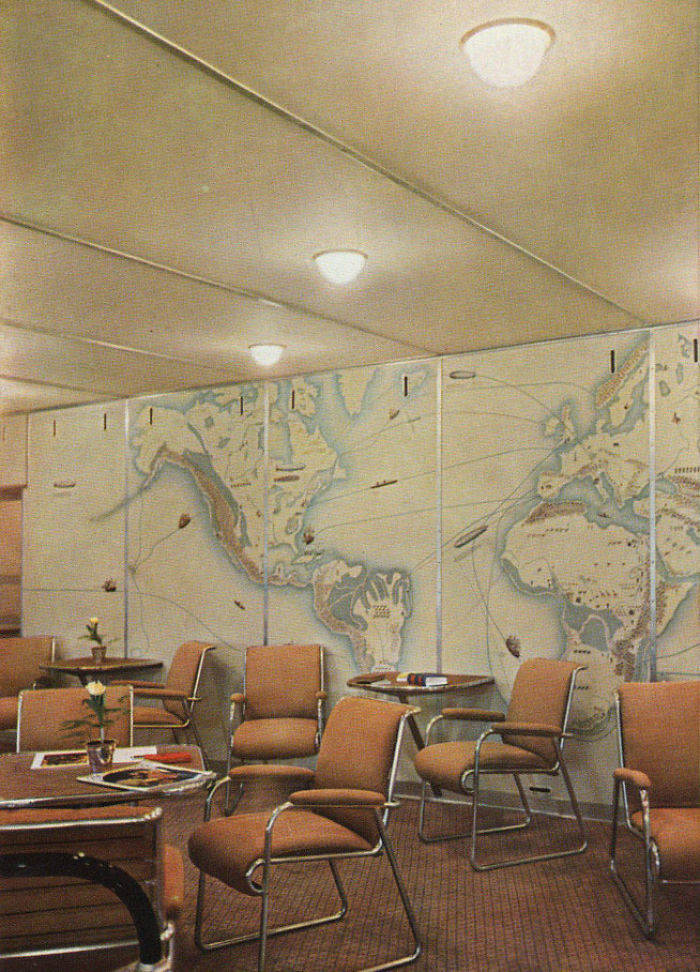

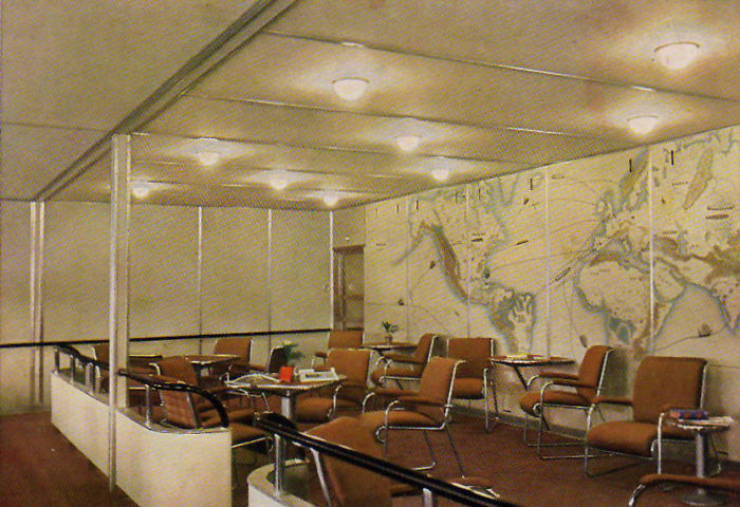

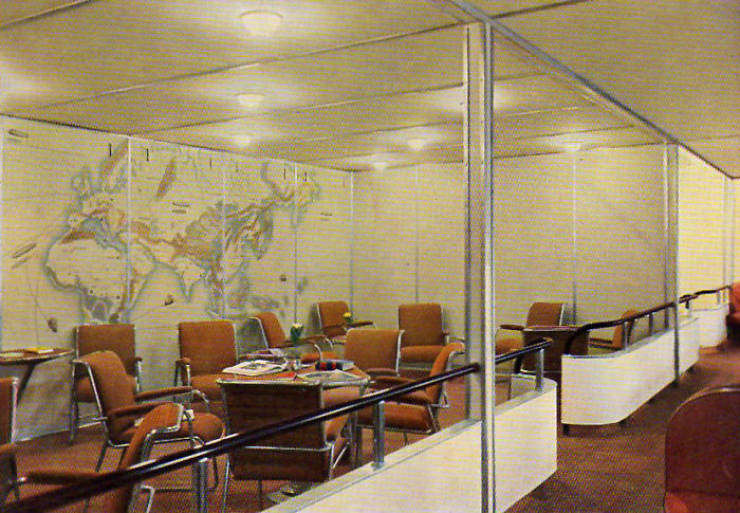

Lounge

The Lounge was approximately 34 feet in length, and was also decorated with a mural by the same Professor Arpke. Only there it were the routes and ships of the explorers Ferdinand Magellan, Captain Cook, Vasco de Gama, and Christopher Columbus, the transatlantic crossing of LZ-126 (USS Los Angeles), the Round-the-World flight and South American crossings of LZ-127 Graf Zeppelin, and the North Atlantic tracks of the great German ocean liners Bremen and Europa.

During the 1936 travel season, the Lounge even had a 356-pound piano, made of Duralumin and covered with yellow pigskin.

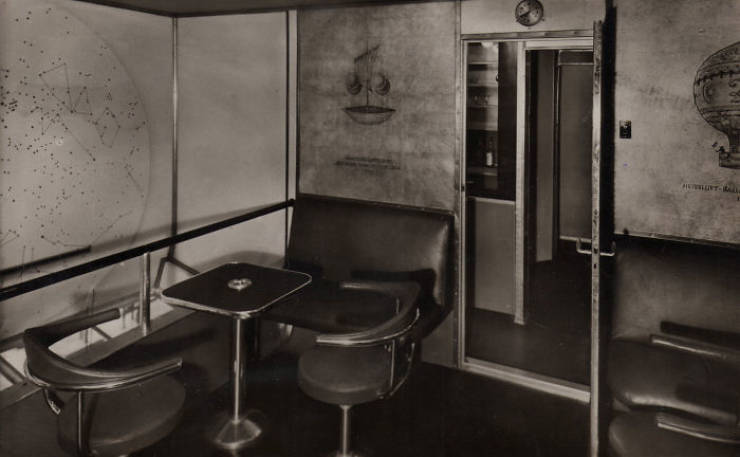

Writing Room

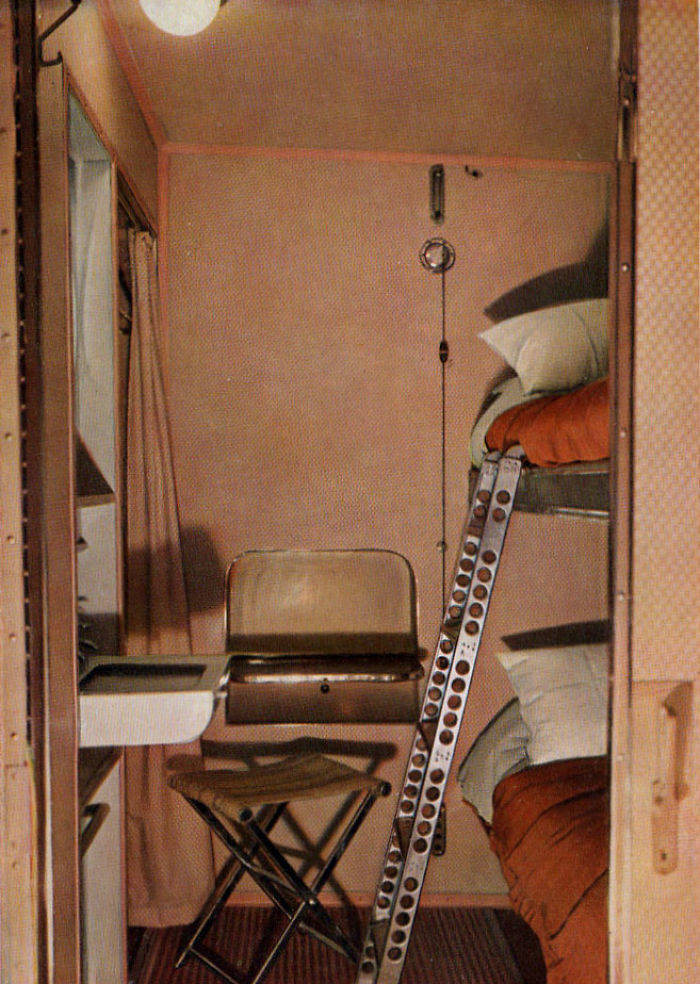

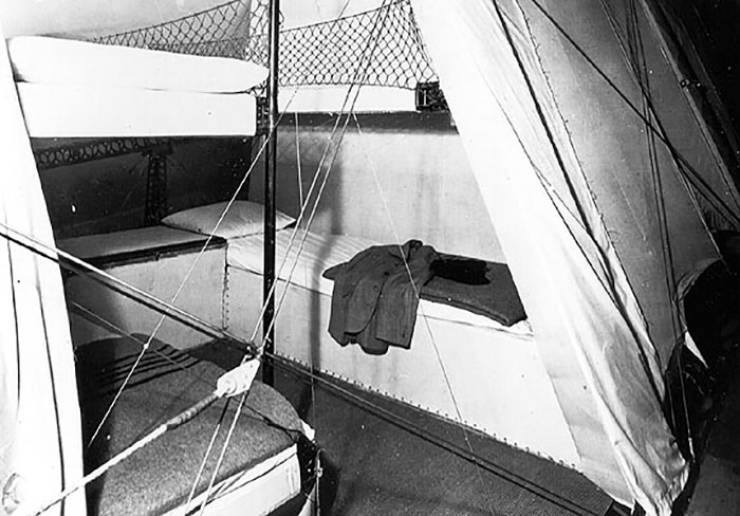

Passenger Cabins on Hindenburg

The Hindenburg was dubbed the ‘world’s first flying hotel.’ Unlike Graf Zeppelin, it contained the passenger accommodation within the hull of the airship. The passenger space was spread over two decks, known as ‘A Deck’ and ‘B Deck.’

The aircraft was originally designed to have 25 double-berthed cabins at the center of A Deck, accommodating 50 passengers. After its inaugural 1936 season, however, 9 more cabins were added to B Deck for 20 extra passengers.

The walls and doors of the cabins were made of a thin layer of lightweight foam covered by fabric. The living spaces came in one of three color schemes: light blue, grey, or beige. Each A Deck cabin had one lower berth which was fixed in place, and one upper berth which the passengers could fold against the wall if they needed more space.

None of the cabins, however, had toilet facilities. Both male and female toilets were available on B Deck below, as was a single shower with a weak stream of water, “more like that from a seltzer bottle” than a shower, according to Charles Rosendahl.

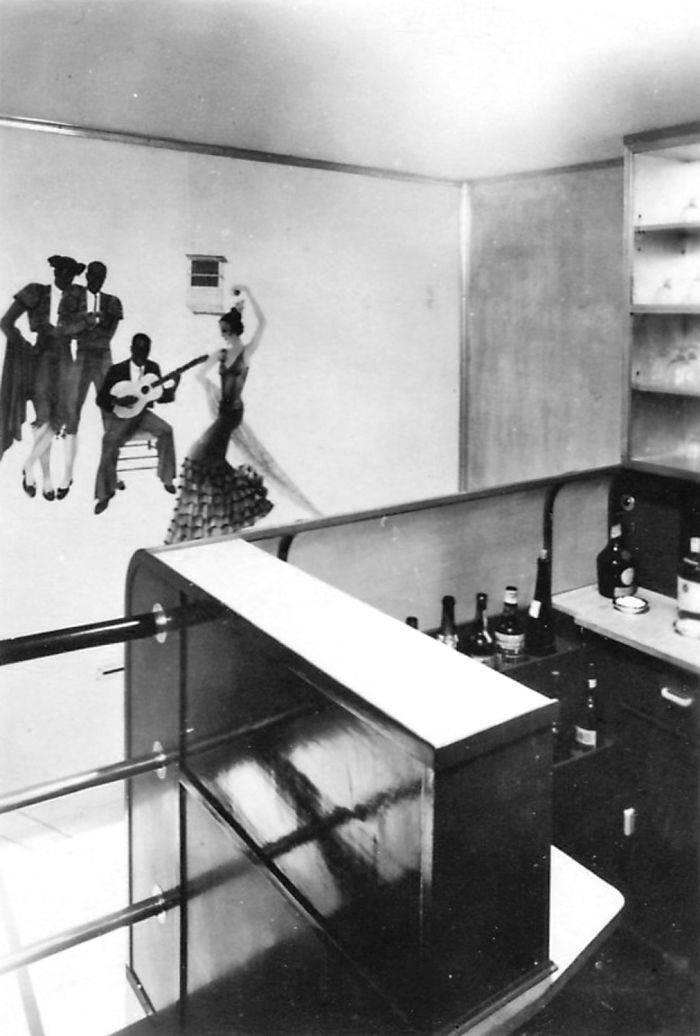

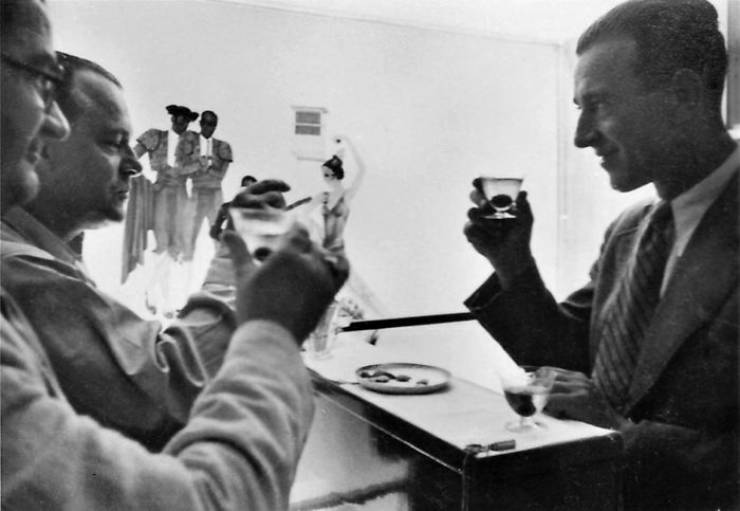

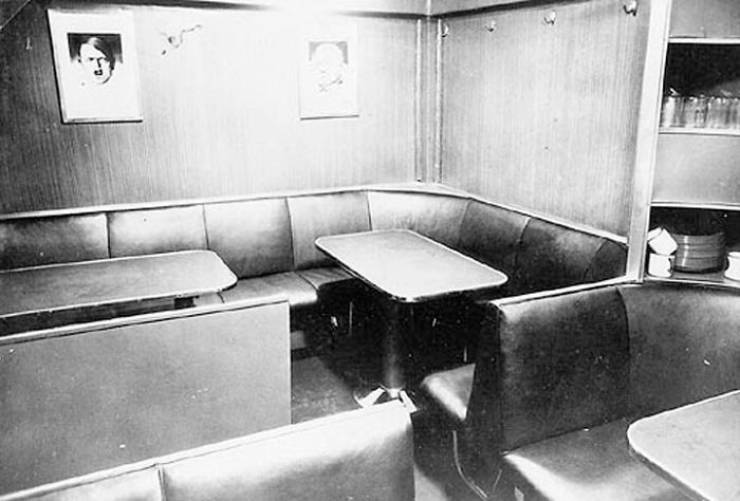

The Smoking Room

One of the most surprising areas aboard a hydrogen airship was the smoking room. However, it was kept at higher than ambient pressure, so in case of a leak, the hydrogen couldn’t enter the room. Furthermore, its associated bar was separated from the rest of the ship by a double-door airlock. There was one electric lighter, since no open flames were allowed aboard the ship.

The Bar

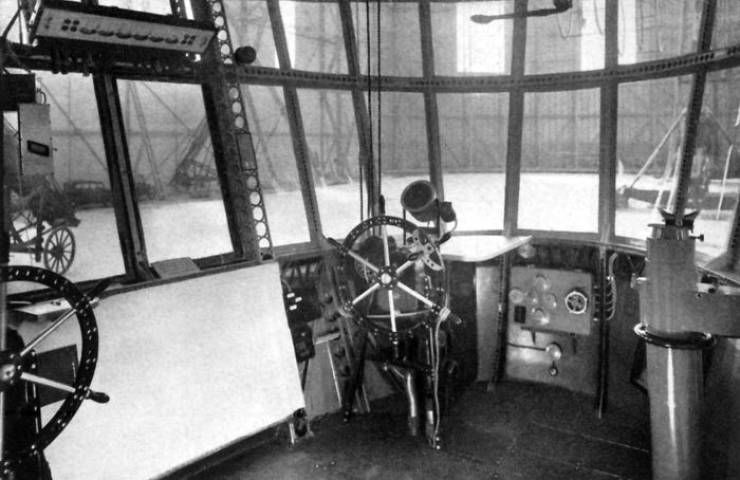

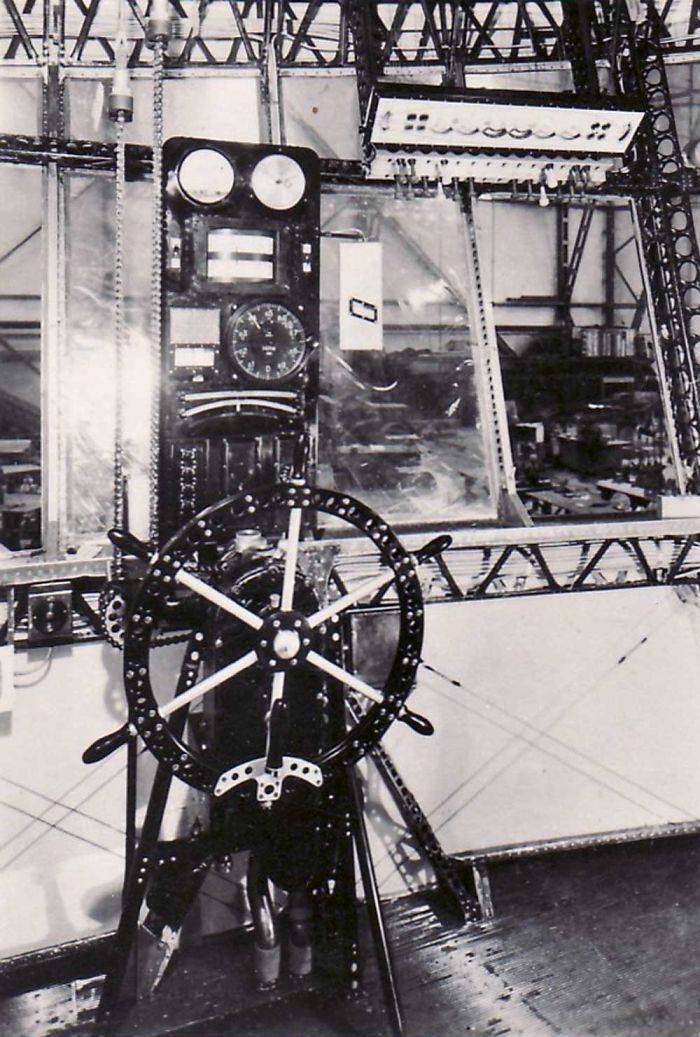

Control Car, Flight Instruments, and Flight Controls

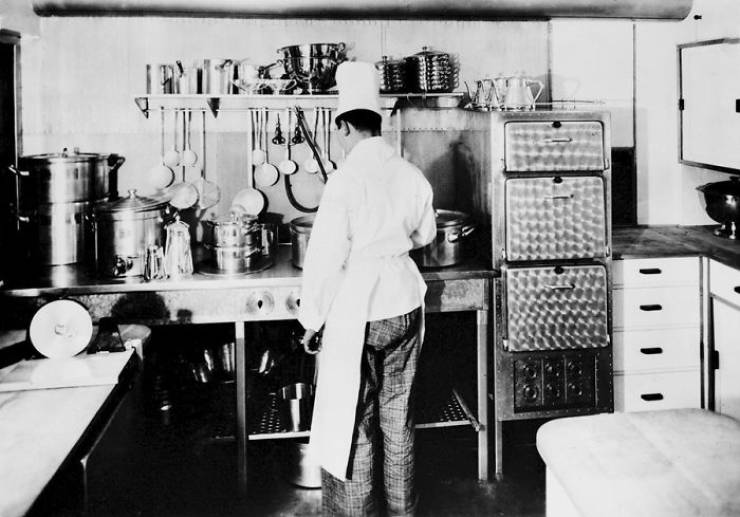

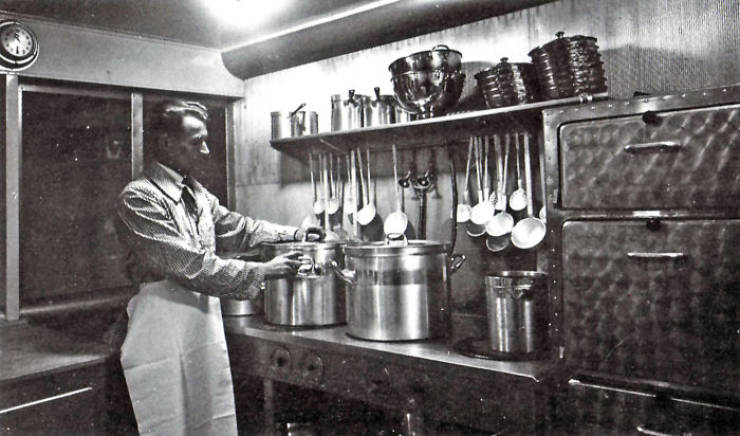

Crew Areas and Keel

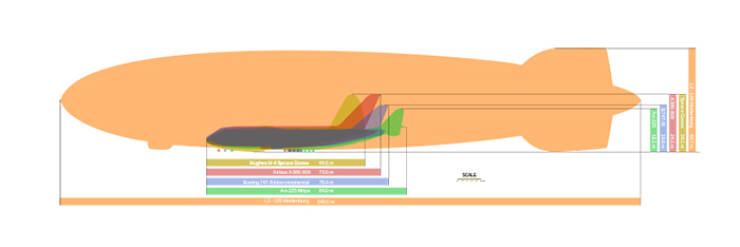

The Hindenburg was three times longer and twice as tall as a Boeing 747

On the 6th of May 1937, the German passenger airship LZ 129 Hindenburg caught fire and was destroyed during its attempt to dock with its mooring mast at Naval Air Station Lakehurst. It had 97 people (36 passengers and 61 crewmen) on board and there were 36 fatalities (13 passengers and 22 crewmen, 1 worker on the ground).

The disaster was the subject of spectacular newsreel coverage, photographs, and Herbert Morrison’s recorded radio eyewitness reports from the landing field, which were broadcast the next day. The event shattered public confidence in the giant, passenger-carrying rigid airship and marked the abrupt end of the airship era.