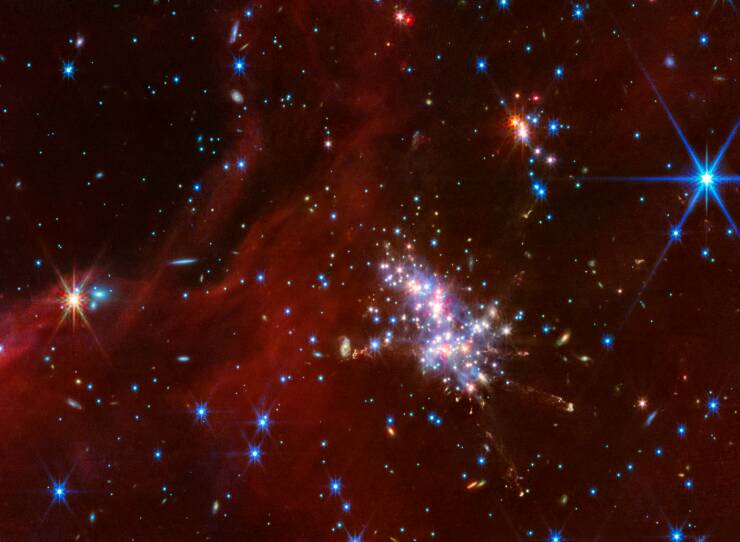

The Flame Nebula lies in the Orion Molecular Cloud Complex and is home to cosmic objects that are not quite planets, but are also so small their cores can’t sustain fusing hydrogen like full-fledged stars do – brown dwarfs.

A Webb view of part of the Flame Nebula. The image contains a mixture of reds, blues and browns, and shows red, blue, and white stars.

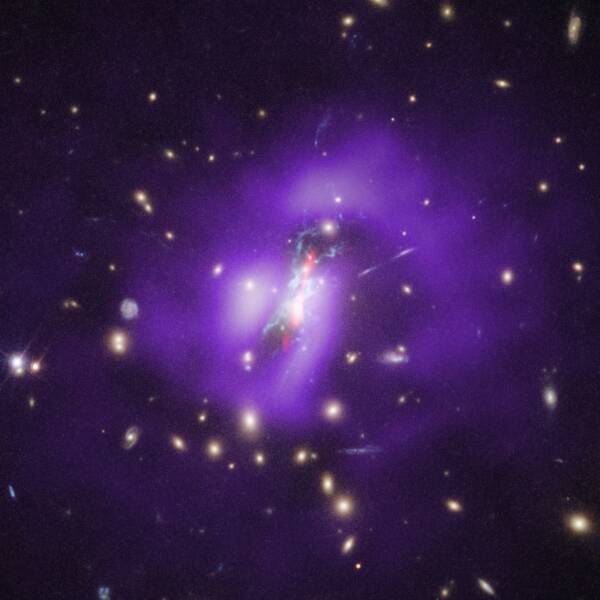

Webb’s infrared sensitivity has helped map the cooling gas that was a missing component in understanding the atypically high rate of star formation within the Phoenix galaxy cluster.

A binary pair of actively forming stars is responsible for this shimmering hourglass of gas and dust.

Millions of years from now, when the stars have finished forming, and have swept the area clean, they may each be about the mass of our Sun. All that may remain is a tiny disk of gas and dust where planets may eventually form.

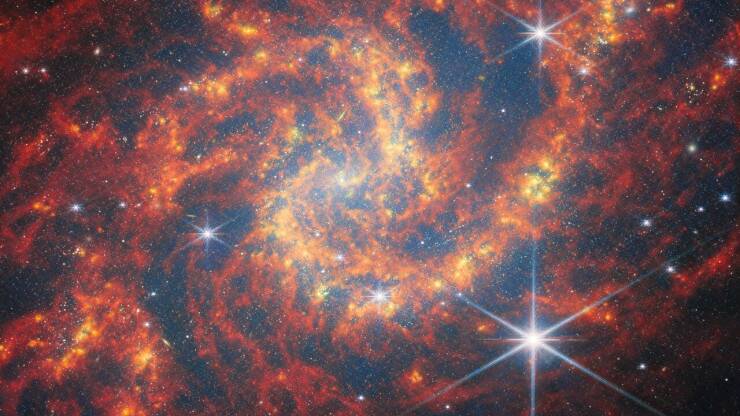

Webb’s new view of barred spiral galaxy, showcasing the light from clouds of hydrogen gas heated by young stars, as well as the stars themselves.

The spikes emanating from the star are called diffraction spikes – patterns produced by light bending around the sharp edges of a telescope.

Isolated from the influence of larger galaxies like the Milky Way and Andromeda, Leo P formed stars early on, and then stopped shortly after a period known as the Epoch of Reionization.

Most dwarf galaxies with star formation that shuts down, never resume it. Unusually Leo P did start forming new stars again.

M74, also known as the Phantom Galaxy.

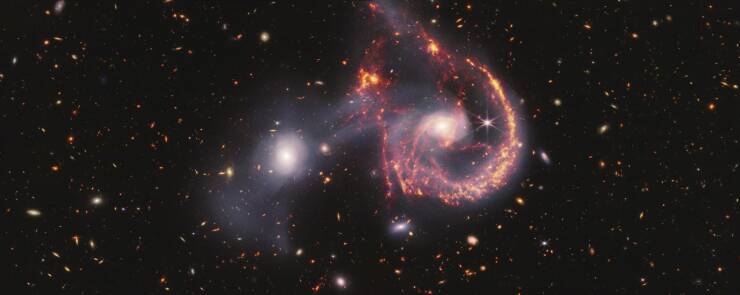

A pair of interacting galaxies.

Astronomers call this region the “Extreme Outer Galaxy” with Digel Clouds 1 and 2 located 58,000 light years away from the Galactic Center. (For context, we are 26,000 light years from the center of the Milky Way). Webb observations now allow scientists to study star formation out there with the same level of detail as within our own solar neighborhood.

These eyes are actually the cores of two galaxies. The smaller spiral galaxy on the left is IC 2163. It has been slowly “creeping” behind the larger galaxy, NGC 2207. It’s possible this pair will swing by one another repeatedly over the course of many millions of years.

Their cores and arms might eventually meld, leaving behind completely reshaped arms, and an even brighter cyclops-like “eye” at the core.

Webb’s sharp infrared vision lets us peer through the dusty veil to reveal newborn stars, brown dwarfs, and planetary mass objects. Many of the young stars in this image are surrounded by discs of gas and dust, which may eventually produce planetary systems.

This side-by-side comparison shows a Hubble image of the massive star cluster NGC 346 (left) versus a Webb image of the same cluster (right). While the Hubble image shows more nebulosity, the Webb image pierces through those clouds to reveal more of the cluster’s structure.

Here’s Webb’s stunning new mid-infrared image of M104. This bright core of the galaxy is dim in this view (the first slide), revealing a smooth inner disk as well as details of how the clumpy gas in the outer ring is distributed.

This image compares the view of the famous Sombrero Galaxy in mid-infrared light (top) and visible light (bottom).

The James Webb Space Telescope’s MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) reveals the smooth inner disk of the galaxy, while the Hubble Space Telescope’s visible-light image shows the large and extended glow of the central bulge of stars.

This mid-infrared image from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope excels at showing where the cold dust, set off in white, glows throughout these two galaxies, IC 2163 and NGC 2207.

The telescope also helps pinpoint where stars and star clusters are buried within the dust. These regions are bright pink. Some of the pink dots may be extremely distant active supermassive black holes known as quasars.